Sports Direct’s owner, Mike Ashley, chose a blustering man-of-the-people line when defending his company’s working practices before MPs on the business, innovation and skills select committee yesterday.

Here was a man who frequently eats in the staff canteen. He walks the shop floor every week to keep in touch with the workforce, flying in by personal helicopter. He looked wounded when challenged on the Dickensian conditions he has presided over, exposed in devastating detail by the Guardian last year and further catalogued to the committee by the union Unite.

“I like to think I am kind to the right people,” Ashley told the MPs. Yet there had been 110 ambulance call-outs to his main warehouse site in just over three years as workers suffered chest pains, stroke, injury, and five births or miscarriages – including one woman delivering her baby in the toilet – such was the fear, according to the union, of losing your job if you took time off under Ashley’s six-strikes-and-you’re-out regime.

One of the two labour agencies Sports Direct uses for a permanent supply of 3,000 temporary workers, employed effectively on zero-hours contracts, had already been prevented from operating in the food sector by the Gangmaster Licensing Authority. Yet Ashley was shocked by the allegations made that the time staff spent queuing to be partly strip-searched by security guards before leaving the factory had driven wages below the legal national minimum wage per hour, or that female workers were sometimes asked for sexual favours in return for longer hours.

That’s repugnant, he said, thumping the table. If Sports Direct was abusing workers in chasing named individuals over the public address system, it deserved the cane. Thump again. I’m just one human being; I’m not Father Christmas; the business has grown so big I can’t be all over the oil tanker; I’m not an expert in employment; be reasonable, he pleaded.

Any sense that Ashley, the executive deputy chairman, accepted responsibility for the effects of his business model on those who worked for him appeared lacking. Absent too was any notion that they were people with rights; he had not met the union because he thought he could do a better job for employees than their own representatives.

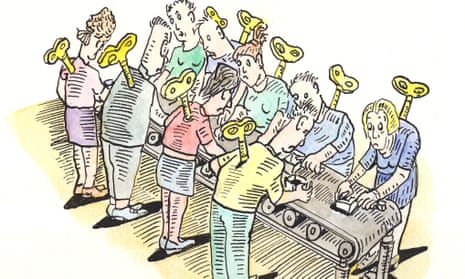

It was a colourful performance. MPs gave him enough rope, and he hanged himself. But in a way, the language used by the directors of Sports Direct’s labour agencies, who appeared just before him, cut more chillingly to the core. They talked of the weekly “average attrition” in worker numbers, and the constant need for up to “four thousand heads”. Because in this brave new world of casualised work, ordinary people are dehumanised, reduced to disposable units of production.

Sports Direct could, like many other businesses with a need for a 365-day-a-year, 24-7 workforce, employ most of its workers directly. But Ashley told MPs he would not do that. Outsourcing employment to agencies diffuses responsibility. Zero- or short-hours contracts guaranteeing only 336 hours a year keep workers under control. If you complain, there’s no need for disciplinary procedures: there may just be no more hours for you.

Competitive tendering in privatised public services has all too often had the same effect – a relentless driving down of costs that translates into fewer people doing more work for the same pay, in more precarious employment.

The model has spread, and unions warn that a similar deterioration in conditions can be seen across sectors from hospitality and catering to retail, transport, logistics and manufacturing.

It is possible to treat workers like this only if you stop seeing them as people and regard them as “other”.

At the same time, chief executives are now paid on average nearly £5m a year in the UK, or 183 times what the average British worker receives.

They expect to join the class of the super-rich – because they’re worth it – taking out of companies the sort of money that enables them to inhabit a chauffer-driven or helicopter-piloted bubble, insulated from the deprivations of those on the factory floor. In this narrative profits are the fruit of executive genius, to be offshored, rather than of a collective effort, to be equitably shared.

Sports Direct may be on one extreme – and by Ashley’s own admission inefficient, because it’s not yet fully automated – but it is not alone. The brutalisation of labour has been a defining characteristic of neoliberal economics. Workers in another retailer distribution centre have described to me being required to wear computerised wristbands that measure how many arm movements they make while picking goods for dispatch. Like electronic tags, these can detect when their strike rate falls below target, and send them an instant warning text.

In the US, Oxfam has recorded further indignities now being imposed in mainstream meat factories, where assembly lines run so fast that even a short toilet break disrupts production. Staff are meant to signal for a “floater” or relief worker to take their place before leaving to go to the toilet, but they told researchers they are often denied a break, so that some have taken to wearing Pampers in case they need to urinate or defecate while on the line.

This growing degradation of the workforce has not occurred in a vacuum. It is the flip side of the same coin that has flight of capital, tax-dodging and excessive executive pay stamped on its other side.

MPs wanted to know whether the law had been broken – and if so, why it wasn’t being enforced. The magnate promised to solve the problem of searching workers pushing them below the legal minimum wage by speeding up security, and perhaps even conceding people one free extra minute at the end of their day as if being paid to endure the indignity made it less intolerable.

But of course, important though employment law is, it has little to do with solving the real problem, which is about power relations that have become so skewed towards those at the top that almost anything goes for those at the bottom of the pile. The only way for workers to change that is to exercise collective muscle – which is perhaps why Ashley has declined to meet the union Unite, except at his company’s annual general meeting.